-

0:00/24:20

The Tale of the Poor Murdered Woman - tracing the real events behind a classic English folk song with Shirley Collins.

In 2013 I asked the eminent folk singer Shirley Collins if she would reflect on the folk song The Poor Murdered Woman - a true story of the discovery of the body of an unidentified woman on Leatherhead Common, Surrey in 1834. We went on a journey to try and find out who this woman was, how and why poor women were often so vulnerable, then and now, and where she may have been buried. Simon Houlihan and I produced this as a feature for Folk Radio UK. With thanks to Alun Roberts (Leatherhead Museum) and veteran BBC newsreader Vaughan Savage. Have a listen ..

The Tale of the Poor Murdered Woman – an interview with Shirley Collins for Folk Radio.

Shirley Collins and the Albion Country Band’s groundbreaking album No Roses (1971) included a memorable version of the bleak tale of The Poor Murdered Woman. Written in the 1830s about real events on Leatherhead Common, the programme takes Shirley Collins back to when she first heard the song in the early 1960s, how the song has stayed with her through the decades - and unearths new information about the fate of the poor murdered woman with Shirley Collins and local historian Alun Roberts seeking out the spot where she was buried in a pauper’s grave in Leatherhead’s parish churchyard on 15th January 1834.

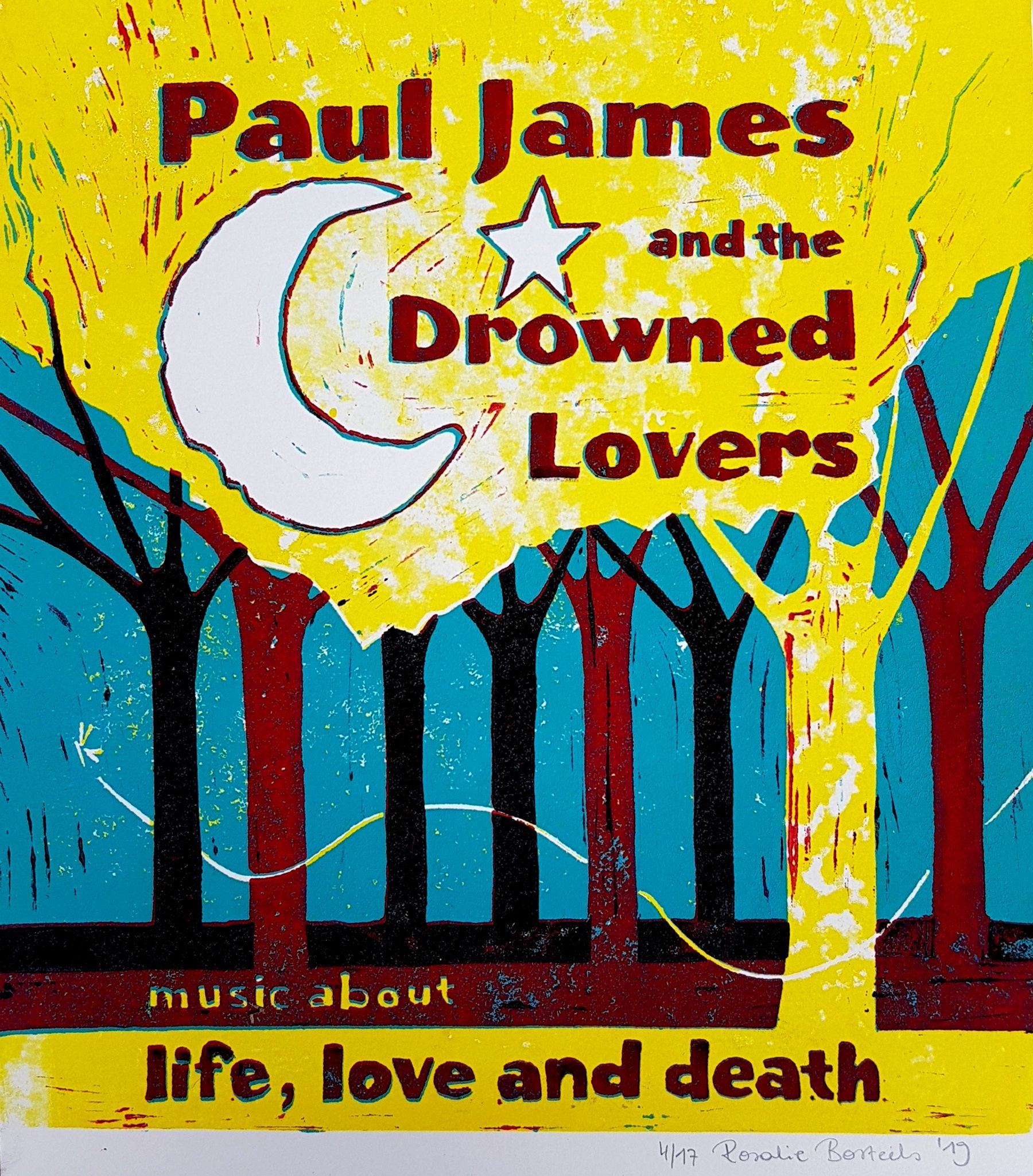

Presented by Paul James. Featuring Shirley Collins, Alun Roberts and Vaughan Savage. Produced by Simon Houlihan and Paul James. February 2013.

The Times, Tuesday, January 14. 1834

SUPPOSED MURDER. While the Surrey Union Fox Hounds (which are under the direction of H.Combe Esq.) were out hunting on Saturday last on Leatherhead Common, a most extraordinary and horrid circumstance occurred, which at present is involved in great mystery. About 12 o’clock in the day, as the huntsman (Kitt) was beating about for a fox, the hounds suddenly made a dead set at a clump of bushes on the common. As no fox made his appearance, the huntsman whipped the dogs off, but they still returned to the bushes, and, smelling all round would not leave. Supposing there was a fox which would not break cover, the huntsman, & c., beat the bushes, and in doing so, to their astonishment and horror, they discovered the body of a woman in a state of decomposition, so much so, that attempting to remove it was found to be impracticable. A person was placed to watch the remains, and information was sent to Dr. Evans, of Leatherhead, who promptly attended. On examining the head, a severe wound was found, and from the general appearance of the body it is supposed to have lain there several months. It was placed in a shell and removed to the Royal oak, on the common, where a coroner’s inquest is summoned to assemble this day (Monday). Various rumours are afloat some stating that the unfortunate woman was the wife if a travelling tinker.

The Poor Murdered Woman – the song

It was Hanky the squire as I've heard men say

Who rode out a-hunting on one Saturday

They hunted all day but nothing they found

But a poor murdered woman laid on the cold ground

About eight o'clock, boys, our dogs they throve off

On Leatherhead Common and that was the spot

They tried all the bushes but nothing they found

But a poor murdered woman laid on the cold ground

They whipped their dogs off and they kept them away

"We do think it proper that she should have fair play"

They tried all the bushes but nothing they found

But a poor murdered woman laid on the cold ground

They mounted their horses and they rode off the ground

They rode to the village and alarmed it all around

"It is late in the evening, I'm sorry to say

She cannot be removed until the next day"

The next Sunday morning about eight o'clock

Some hundreds of people to the spot they did flock

For to see the poor creature, your hearts would have bled

Some cold-hearted violence came into their heads

She was took off the Common and down to some inn

And the man that has kept it, his name is John Simms

The coroner was sent for, the jury they joined

And soon they concluded and settled their mind

The coffin was brought, in it she was laid

And took to the churchyard of this court Leatherhead

No father nor mother nor no friend I'm told

Came to see the poor creature laid under the ground

So now I conclude and I'll finish my song

And those that have tarried shall find themselves wrong

To the last day of Judgement a trumpet shall sound

And their souls not in heaven, I'm afraid, can’t be found.

The song was collected in the late 19th century by Lucy Broadwood (1858 - 1929). As one of the founder members of the Folk Song Society and Editor of the Folk Song Journal, she was one of the main influences of the English folk revival of that period. She was an accomplished singer, composer, piano accompanist, and amateur poet and was much sought after as a song and choral singing adjudicator at music festivals throughout England.

The Poor Murdered Woman – the facts

Alun Roberts, Leatherhead Museum. January 2013.

The circumstances of the discovery of the body were very much as described in the song. The inn the body was taken to was the nearby Royal Oak, a coaching inn which still exists, although it has been rebuilt in a slightly different location. The landlord at the time was indeed John Simms, who later became a brickmaker. There was also a farm attached, where the writer of the song, James Fairs, probably worked. (He was listed as an agricultural labourer in the 1841 Census, later becoming a brickmaker in the adjacent Woodbridge brickworks, which was in existence well into the 20th century. There was a huge demand for bricks and tiles (and flower pots) at the time, there being no local building stone other than flint (there were two other brickfields). The clay pits can still be seen in Teazle Wood, an area of ancient woodland which has recently been saved from development and is still common land.) Leatherhead Common was (and still is, although much reduced) a large area of common land to the north of the town. The actual Common Field, used for agriculture, was to the south of the town. Leatherhead Common, which gave its name to the whole of the northern part of the town, was poor quality land unsuitable for farming.

George Barnard Hankey of Fetcham Park, who came from a wealthy banking family but preferred to live a life of leisure, was the Lord of the Manor of Fetcham and Master of the Surrey Union Hunt. Their dogs, mentioned in the song, were kept on his land in what is now called Kennel Lane. The other gentleman named in press reports, H. Coombe, was from the brewing family of that name and lived in Cobham (they were later taken over by the dreaded Watneys, which became known as Watney, Coombe and Reid).

The doctor who was summoned, Abel Evans, had his surgery in Church Street and was the oldest practitioner in town - he was dead by the time of the 1841 Census.

A rumour quickly spread that the body was that of the wife of a travelling tinker - the locals must have remembered them camping on the Common the previous summer and they would no doubt have visited the local pubs. The police, only formed five years before in 1829, issued handbills with a description of the suspect and as a result a young girl from Tunbridge Wells came forward and said she remembered passing the night with some travellers in a barn in Dorking, one of whom, Peter Bullock, alias Williams, confessed while drunk to have killed his sweetheart Nancy with a hammer after a night drinking in Leatherhead (probably in the Plough rather than the Royal Oak, it being the pub favoured by working men). However, the police were under great pressure to find a culprit - there had been a number of well publicised murders and highway robberies in the area around that time and it is on record that innocent men were being arrested and charged for the crimes, only to be found not guilty for lack of evidence. There is a record of Bullock being arrested and remanded in custody at Union Hall Magistrates Court after a preliminary hearing but I have been unable to trace any record of his trial or conviction. He denied being anywhere near Leatherhead at the time and said that he already had a wife (albeit living with another man) and was not in the habit of travelling with any other woman. The only evidence against him would have been the testimony of the girl alone. The case may never have come to court, although I will keep looking. There is no record of his having been hanged or transported. It raised my suspicions when I read that the police claimed that his statement on being arrested was 'I suppose you are taking me for that murder and will hang me'. This (known in the criminal fraternity as verballing) has been a technique used by police since time immemorial when they have no other evidence. At that time the reputation of the police for honesty was untarnished (no longer sadly) and it would been fatal for the accused to say they were lying. Bullock merely said that he had no recollection of saying those words. The identification of the woman as his lover Nancy rests only on the hearsay evidence of the girl. Bullock, like Colin Stagg and Barry George in recent years, may have been arrested for being merely the sort of person who might very well have committed the crime. Miscarriages of justice were not easily rectified in those days, the accused usually having been hanged. The papering of the county with handbills (and indeed the fact that a song was written about the murder) would have created just the sort of atmosphere in which innocent people are arrested and charged on the basis of little or no evidence.

James Fairs son was also a labourer but his grandson George William became quite wealthy and his greengrocers shop (opened in 1899 in the oldest building in the town) was in existence (kept by his descendants) until the 1970s. Fairs Road was named after him when the Leatherhead Urban District Council was formed at the end of the nineteenth century, when he was still well remembered. James' cottage can be seen on maps of the time, adjacent to the Workhouse (which closed in 1838). It was very close to the scene of the crime and he would have known all the details very well. I imagine it was the talk of the town for many months. Leatherhead, like all villages, was noted for gossip (and indeed still is, being a village at heart rather than a small town).

Lisney, who verified the facts of the song when it was recorded in Milford in 1908, was the local blacksmith. He, an old man, clearly remembered the facts of the case. I have a photograph of him.

Paul James

February 2013